Walking the lines in Chile. . . (or the great lost milk glass line)

by Robin Harrison

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", April 1998, page 8

I took a trip to Chile this past winter with my sister Vikki, primarily to

take a few treks in the Andes, visit the wonderful Parque Torres del Paine and

visit Tierra del Fuego. Knowing my propensity to concentrate more on what was

going on 20 feet up on the power poles, rather than the sights of the country,

we made a deal that we would travel together for two weeks and then have a half

week of separate adventure. My independent time was to be spent on my favorite

hobby, and thus hopefully I wouldn't be digging around in the dirt, sneaking up

rotten poles and generally embarrassing Vikki while we were traveling together.

I was mostly successful at keeping this bargain, except on buses, where I spent

much of the time looking at telephone poles until my neck got sore.

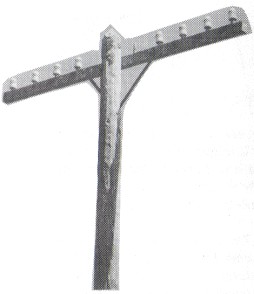

Crossarm of white milk glass tolls?

The truth

is, I wasn't in the country two days before I made a complete nuisance of

myself, because I became convinced that I had found a 50 mile line of milk glass

tolls. Our first trek was planned for a park on the Argentinean side of the

Andes, so on our second day in Chile, we met some friends and took a bus over

the Andes and across the border. While traveling towards the mountains, through

beautiful scenery consisting of farmland with volcanoes on the horizon, I soon

realized that our bus was passing a remarkable phone line insulated with various

brown porcelain and green and clear glass

tolls. Many of the poles looked very old and not

maintained (see photos). Then I saw the most remarkable sight of my insulator

spotting career; some of the tolls were very pale in color, looking white

sometimes and at other times with an opaque pale blue tint.

Crossarm with brown, porcelain and

turquoise plastic insulators.

Before leaving on this trip, I had called Marilyn Albers to get the low-down

on what to expect in Chile, and she indicated that most insulators from this

country were uncommon, but what really got people excited was a handful of milk

glass insulators that had been recovered from Chile. I got very excited; milk

glass tolls! Then I started noticing that

parts of the line were almost exclusively white

tolls, and when the sun was behind them, they definitely gave off a hint of

blue. Had I finally found the mother lode? I sat daydreaming for hours about the

fantastic trades I would make when I got home with my milk glass tolls. There

had to be hundreds of them here. The fact that they were still in use on poles

did not yet intrude into my fantasy world.

A week later on the bus trip back, I

spent absolutely every second watching the poles, and was even more convinced

that this was the milk glass find of the decade. I debated briefly about these

actually being white porcelain tolls, but I knew that white tolls would be very

unusual, I could only think of one U.S. style that had ever been reported. The

blue tint when the sun shone on them indicated that they couldn't be white

porcelain. I started to notice that the poles were very decrepit, and were

actually missing in three and four mile sections. Could this be a line nearing

obsolescence? Then I saw a pole laying on its side and noted the milepost, 41

km. I had a very good idea at that point where I would be spending my half week

on my own.

The following week in southern Chile, I was mostly very faithful to

my bargain, except for stopping at a local telephone company and asking about

insulators. I had seen CD 108.5 on poles outside the city of Punta Arenas and

hoped to get one of these unusual ponies. After an extended debate, one of the

employees remembered that he had some insulators at home and promised to bring

them the next day. He was true to his word and the next day I became the proud

owner of a no-name brown porcelain spool and a modem brown porcelain no-name cable. I decided that my insulator collecting really should wait until

my last week of travel.

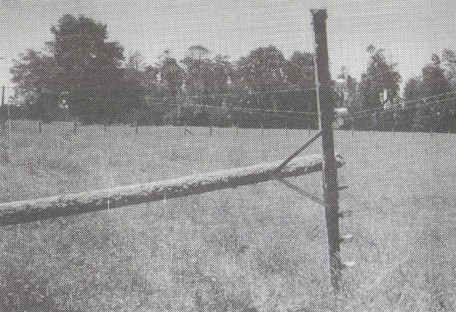

The fallen pole in a field.

After some unbelievably beautiful hiking in Torres del

Paine (although quite a bit of it was spent in the rain) during which we saw

lots of guanacos, rheas, flamingos and quite a few other exotic birds and

plants, we took the long bus ride back to Punta Arenas. The telephone lines in

this part of the country were mostly porcelain spools interspersed with

occasional CD 108.5's and CD 154's. The only exception were two beautiful

Cristelarias de Chile yellow straw CD 202s on one pole, still in use and in

front of a police station; We returned to central Chile and began our

independent travel. I ensconced myself in a hostelaria in a town close to the

telephone line and proceeded with the sacred ritual known to all dedicated

foreign insulator collectors: the trip to the totally incredulous and hopefully

amused local telephone company to ask for insulators. This one was no exception.

When they realized that I was not joking and that my descriptions of my

unbelievable hobby was not the result of bad Spanish (although there was plenty

of that on my part), they assigned me to the very patient and accommodating Jefe

del Lineas (Chief of lines) who took me out to the storage facility. There I

heard the almost universal story about how there had been hundreds of insulators

just a little while ago, but they had all gone to the dump just the week or so before. I heard this in all three towns

I checked in Chile, which

shows how very little foreign countries really differ from our own!

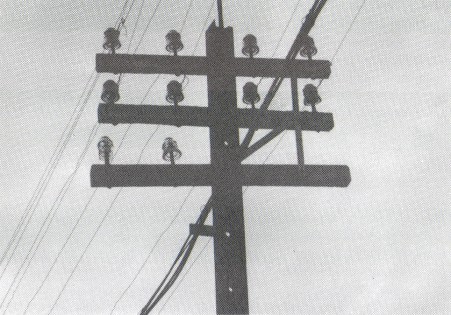

Typical railroad pole, crossarms on old rail.

On the way

over I told him about seeing the milk glass insulators on the poles, and

although he had never seen these, he was game to see if he had any. He first

took me into the new equipment room just to heighten the suspense, showing me

more brown porcelain spools (just to torture me), and then dug down under a huge

pile of advertising material to a milk crate where I heard the happy sound of

insulators banging against each other. He started pulling them out one at a

time, and I was thrilled to see a couple of CD 113 Cristelarias de Chile come

out, although they were pretty banged up. Next came a brown porcelain toll with

an unreported marking (an F inside a circle and square; I was told it stood for

the Fanalosa de Chile in Concepcion). Then came the insulator that made my whole

milk glass fantasy castle come crashing down: he pulled out a lovely pale blue

porcelain toll and handed it to me. Everything was very clear now. The faint

blue tint of the insulators wasn't due to a faint tint in milk glass, the whole

darn insulator was pale blue porcelain. This is the point of time where it really

pays off to be a mud collector. As my visions of rare glass faded into the

dreams they were, my porcelain instincts revved into gear. A blue porcelain

toll, that's something no one has reported before! Then he pulled out an even weirder insulator, a pale blue porcelain almost exactly

like a CD 129. Then came a white European looking cable top insulator with small,

nonstandard threads. Finally he extracted a CD 122 clear insulator marked simply

"No. 16". Life in the box had not been easy, and most of these pieces

had some damage, but I was on my way with my first truly Chilean insulators. He

told me that the line I had seen outside of town was being dismantled, and any

insulators I found on the ground were fair game. My next day was as good as

planned.

Note: The railroads in both Chile and Argentina have clear evidence of

their English heritage. Like the lines in Uruguay described by Bernie Warren,

these were built by the English in the late 1800's. Many sections still had

Cordeaux style insulators, some marked Bullers. In the countryside I spotted

brown porcelain telegraph insulators that could have been recent locally

manufactured porcelain, or could have been early Varley patents (it's hard to

tell from a bus). My next trip to South America will include an extended

railroad hike and hopefully a ride. Sadly, like Uruguay, the railroads in Chile

are falling into terrible disrepair, and many lines no longer run. Their future

is very uncertain, but I hope to ride some of them before they are gone.

I got

up early and headed for the bus station, and located the bus to the Andes. I

told them that I wanted to be dropped off at exactly 41 kilometers out of the

city. The bus assistant gave me a strange look, knowing that there was nothing

out there except trees and open farmland. Fortunately, my Spanish was so bad he

decided to humor me. As we approached the spot, the bus assistant got very

distressed as he looked out on the scenery, which clearly had nothing whatsoever

to interest a foreign visitor. I assured him as well as I could that this was

exactly where I wanted to get off and left the bus for my hike. For the rest of

the day, every couple of hours the bus would go by and honk and everyone on the

bus would wave. I got the strange feeling that everyone riding that day heard

the story of the strange American who had gotten off the bus in the middle of

nowhere and just walked around, or worse, was seen crawling out of the ditches

and blackberry thickets as if he had been rooting around in there for some

reason. I was having too much fun to really worry about it though. I found my

fallen pole, but only one insulator had fallen off, and although I was pretty

certain that the line was abandoned at this point, I couldn't bring myself to

take the wires off the insulators screwed onto the pole. A deal I had from the

phone company was that I was allowed anything on the ground. There were gaps in

the poles ahead where I was certain that poles had been completely taken down,

so I headed down the road.

Blue porcelain insulators waiting to be collected.

Where poles had been pulled out, I sometimes found little piles of whole and

broken insulators. It turned into a typical insulator hunt; at first I stuffed

everything in my pack, and then as it got heavier and heavier, and the day got

closer to hot afternoon (this was February, high summer in Chile), I started

culling the chipped ones, and then the brown ones, and then finally started

throwing back ones in an odd grey color, since it seemed most likely that

collectors would be most interested in the pretty blue colored ones. This

reflected my past trading with Pittsburg U-243's at home, where light blue

out-traded gray by about 6 to 1.

By the time I filled my pack, I realized that

although many of the standing poles had glass insulators on them, I had found

only porcelain ones. The next day, my last, would have to be concentrated on

glass insulators. I waved down a bus, sadly not the one that I had come out on,

and returned to town. As I walked to the hotel, I passed a little

hole-in-the-wall bike repair shop and got a great idea. Somehow I got them to

understand that I had worked in a bicycle shop in the past, and wanted to rent a

bicycle for a day. One of the owners thought this was a grand idea, and agreed

to rent me his own mountain bike for the whole next day for about $10. Now I

could hunt insulators as only a person with complete freedom to travel can do.

Porcelain insulators (l to r): two variants of light blue

tolls, lavender

gray toll, light blue sim CD 129.

Early European style, brown

toll, with Fanalosa marking.

Glass insulators (l to r): four CD-121; yellow tint,

peach tint, near clear,

light green, CD-113;

All Cristalerias de Chile.

Plastic ponies, black and two variants of crackled turquoise.

The next day was one of the finest insulator hunting days I've ever had. I rode out

of town on a bike mechanic's personal bicycle, which was

therefore in excellent shape, on a bright clear day with puffy clouds drifting

by periodically to block sun for a spell. I started tracing the line from the

town back out into the country. There wasn't much on at the sites of downed

poles near the town; everything had been cleaned up. But by the time I had

ridden ten miles, I started to find the occasional insulators in the ditches and

blackberry thickets. The dreaded Himalayan blackberry as well as a very dense

bamboo grass have made serious colonies along the roads in central Chile and

made my searching miserable, some places were literally impossible to travel

through. On the other hand, linemen weren't about to chase insulators into these

thickets either, so they were the best place to look. As usual, linemen had

cleaned up what they could and left the hard to salvage ones. I found a few off

clear No Name "No. 16" tolls, and few light blue tolls and a gray one.

Soon I hit a section with a lot of little plastic insulators, apparently

replacements used a considerable time before. These were mostly very weathered,

with the turquoise ones covered with tiny cracks like an old painting, if they

weren't completely falling apart. Naturally, the uglier black ones were in

excellent condition. I kept quite a few of the ones that were still in one

piece; at least they were light!

I soon came to a section where the men were

taking down poles, and stopped to talk to them. My poor Spanish was not

sufficient to make them understand exactly what I was doing (or they couldn't

believe it), but they also indicated that there were insulators in small piles

for the next mile or so and I was welcome to them. In this area I collected a

number of gray and blue porcelain tolls. I also started to cull considerably,

but decided to keep a few of the gray tolls, as I had thrown all but one away

the day before. I regret not collecting more of these, since it has turned out

to be an unusual color almost a lavender gray (unique to this insulator) that has

attracted quite a bit of attention.

As before, the chipped and cracked or poor

old plain brown insulators were stuck back in the bushes and only the better

colored ones were saved. This part of the line seemed to have few glass

insulators, but the killer was that about every third standing pole had a single

green glass toll or exchange, and none had shown up along the road. By late

afternoon, I was carrying a pack full and headed home. I was watching for a pole

I had seen the day before which had broken off and fallen upside down from a

hill near a fruit stand. I figured out the location, but it took a while to find

the crossarm, which had been completely stripped and there were no insulators in

sight. A half a mile later, I noticed that poles were missing down a hill in a

swamp completely surrounded by blackberries. I found a cow path and popped

through to find a pole laying on the ground with 4 insulators still in place, including two light lemon tinted No. 16's with the

intertwined C logo of Cristalerias de Chile. That was enough for one day. The

shoppers at the fruit stand were clearly amazed at my condition and as I looked

myself over, I saw that I was completely covered with leaves and dirt and my

bare arms and legs looked like I had been wrestling angry cats for a few hours.

It was time to head home, and try to avoid as many people as possible.

I left

town early the next morning, taking the bus to a nearby city to catch my plane

to Santiago to meet my sister. It took two trips to get my gear and insulators

to the bus station. I was REALLY glad I had left my camping and backpacking gear

at the Santiago airport. I was starting to get a little worried about getting

everything home on an international flight. The bus pulled out of town, and I

sat back thinking that in those two days I had managed to get every style and

color of insulator I had seen on the poles, except for the light green glass

toll. I comforted myself that it had been a nearly perfect two days. The bus was

just leaving the outskirts of town on a major highway when I sat upright in my

seat. Off to the right of the bus across a field, I could see a crossarm

hanging from one wire in the middle of the field at about chest level, with

three green glass insulators on it. Oh well, my bags were stashed under the bus

and there was no way to get off now. But it was a long bus ride, and I soon

convinced myself that I had to go back and get those insulators. I soon had the

bus schedule out and calculated that if I could get off the bus, stash my stuff

in baggage storage at the bus station, get on the next bus, briskly walk three

miles out of town, snag the insulators without getting caught, get back to the

bus station in time for the last bus back to the city, I had just enough time to

pull it off and still have time to get a hotel room.

Four hours later, I had

arrived at the crossarm, which apparently had literally fallen off the pole and

snagged by a broken wire on a nearby fence. Well, it wasn't exactly on the

ground, but I convinced myself that I would have been fair game in very short

time. I quickly saw that one insulator was completely shattered in the fall, but

there were two nice ones and one with a fair sized chip; I grabbed all but the

shattered one. I turned back to the road and saw that I had a large audience in

what appeared to be a fairly popular park. I became somewhat nervous at this

point. It was early evening, and if the police decided to check me out, I would

have no alibi until the next morning when the phone company opened, but by then

I would have missed my plane, starting a cascade of missed flights and

connections that could be a disaster, not to mention leaving my sister at the

Santiago airport wondering where I was (actually she would probably be able to

make a good guess!). To my great relief, the next local bus that passed was going to the bus station, and I was on my way. Five miles out of town we hit

a police road block, and my blood pressure rose to dangerous levels until it

became clear they were checking for safety violations on the bus. I settled into

my seat, deliberately sitting on the side of the bus opposite the telephone

line. I just couldn't stand to see any more downed insulators, and my time was

really up. Sadly, I had forgotten the railroad was on the opposite side and

became painfully aware that it too was in a bad state of repair. What was that?

Were those crossarms piled up like cordwood? I tried to read.

The next day

started a seemingly unending 30 hours of airports and planes that are best left

undescribed. The one high point was strolling through customs in Miami with only

a smile and a wave, no bag search. I have included a photo of how I managed to

carry my insulators as well as backpacking gear, which I am calling the

insulator collectors double backpack technique. Thankfully, my bags were not

weighed and I carried the small backpack (filled with insulators) as a carry-on.

It was my faithful (if backbreaking) friend for the next 30 hours.

One way to get 40 lhs. of insulators home on a plane.

|